Inline processing of network packets using GPUs is a packet analysis technique useful to a number of different applications.

Inline processing of network packets using GPUs is a packet analysis technique useful to a number of different applications.

The inline processing of network packets using GPUs is a packet-analysis technique useful to a number of different application domains: signal processing, network security, information gathering, input reconstruction, and so on.

The main requirement of these application types is to move received packets into GPU memory as soon as possible, to trigger the CUDA kernel responsible to execute parallel processing on them.

The general idea is to create a continuous asynchronous pipeline able to receive packets from the network card directly into the GPU memory. You also dedicate a CUDA kernel to process the incoming packets without needing to synchronize the GPU and CPU.

An effective application workflow involves creating a continuous asynchronous pipeline coordinated between the following player components using lockless communication mechanisms:

- A network controller to feed the GPU memory with received network packets

- A CPU to query the network controller to get info about received packets

- A GPU to receive the packets info and process them directly into GPU memory

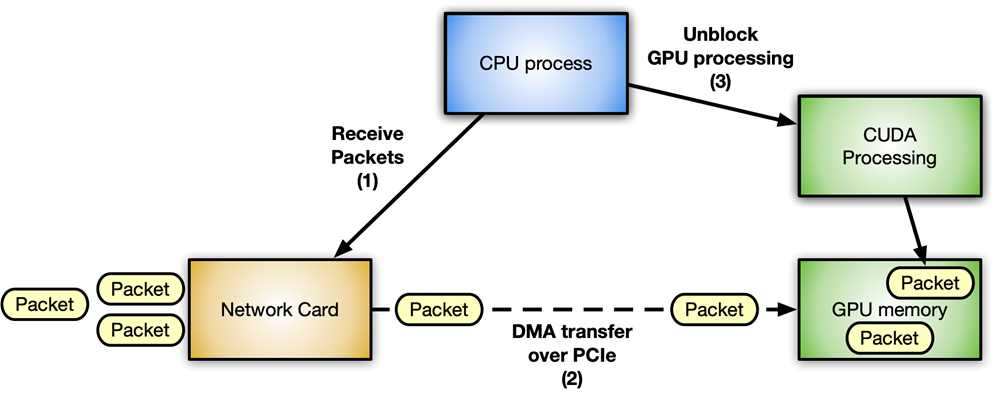

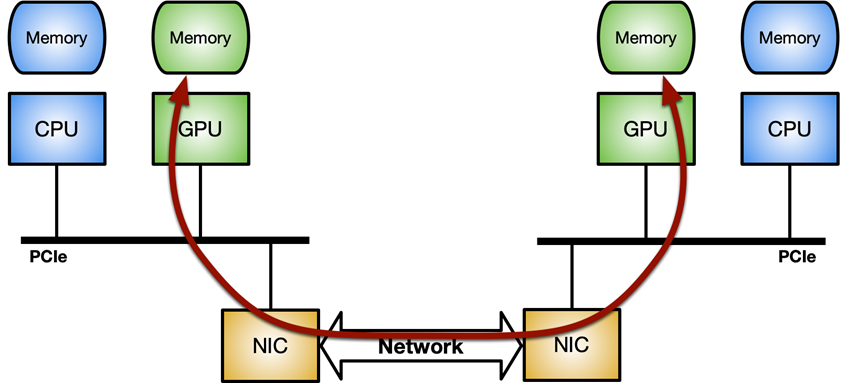

Figure 1 shows a typical packet workflow scenario for an accelerated inline packet processing application using an NVIDIA GPU and a ConnectX network card.

Avoiding latency is crucial in this context. The more the communications between different components are optimized, the more the system is responsive with increased throughput. Every step has to happen inline as soon as the resource that it needs is available, without blocking any of the other waiting components.

You can clearly identify two different flows:

- Data flow: Optimized data (network packets) exchange between network card and GPU over the PCIe bus.

- Control flow: The CPU orchestrates the GPU and network card.

Data flow

The key is optimized data movement (send or receive packets) between the network controller and the GPU. It can be implemented through the GPUDirect RDMA technology, which enables a direct data path between an NVIDIA GPU and third-party peer devices such as network cards, using standard features of the PCI Express bus interface.

GPUDirect RDMA relies on the ability of NVIDIA GPUs to expose portions of device memory on a PCI Express base address register (BAR) region. For more information, see Developing a Linux Kernel Module using GPUDirect RDMA in the CUDA Toolkit documentation. The Benchmarking GPUDirect RDMA on Modern Server Platforms post provides more in-depth analysis of GPUDirect RDMA bandwidth and latency in case of network operations (send and receive) performed with standard IB verbs using different system topologies.

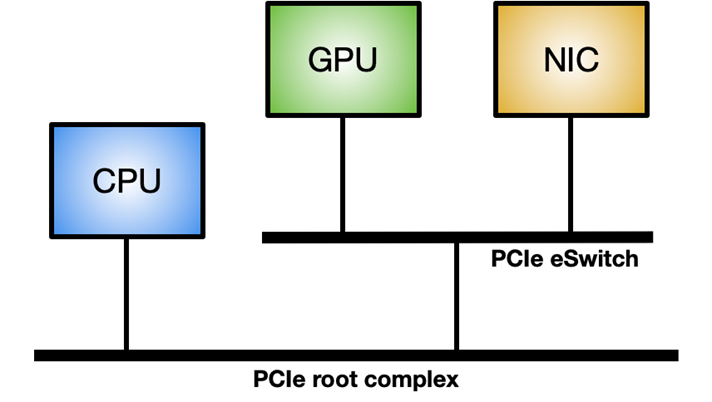

To enable GPUDirect RDMA on a Linux system, the nvidia-peermem module is required (available in CUDA 11.4 and later). Figure 3 shows the ideal system topology to maximize the GPUDirect RDMA internal throughput: a dedicated PCIe switch between GPU and NIC, rather than going through the system PCIe connection shared with other components.

Control flow

The CPU is the main player coordinating and synchronizing activities between the network controller and the GPU to wake up the NIC to receive packets into GPU memory and notify the CUDA workload that new packets are available for processing.

When dealing with a GPU, it’s really important to emphasize the asynchrony between CPU and GPU. For example, consider a simple application executing the following three steps in the main loop:

- Receive packets.

- Process packets.

- Send back modified packets.

In this post, I cover four different methods to implement the control flow in this kind of application, including pros and cons.

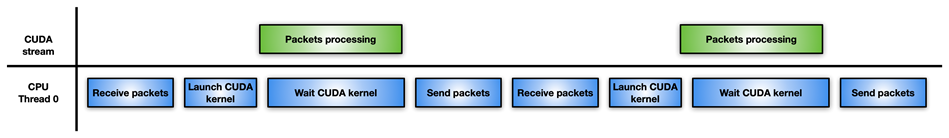

Method 1

Figure 4 shows the easiest but least effective approach: a single CPU thread is responsible for receiving packets, launches the CUDA kernel to process them, waits for the completion of the CUDA kernel, and sends the modified packets back to the network controller.

If packet processing is not so intensive, this approach may perform worse than just processing packets with the CPU, without the GPU involved. For example, you might have a high degree of parallelism to solve a difficult and time-consuming algorithm on packets.

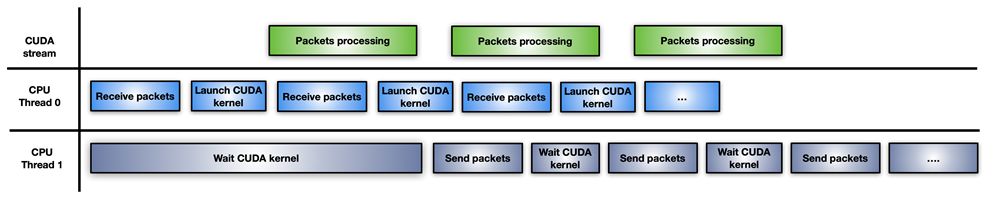

Method 2

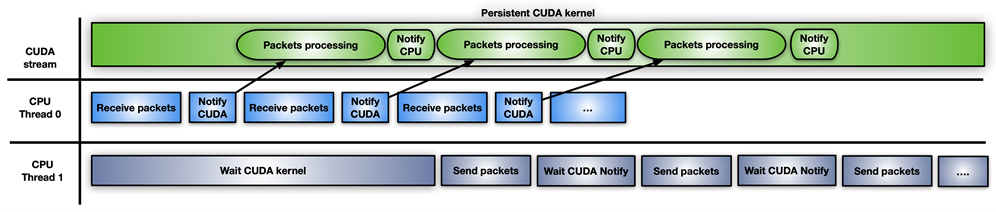

In this approach, the application splits the CPU workload into two CPU threads: one for receiving packets and launching GPU processing, and the other for waiting for completion of GPU processing and transmitting modified packets over the network (Figure 5).

A drawback of this approach is the launch of a new CUDA kernel for each burst of accumulated packets. The CPU has to pay for CUDA kernel launch latency for every iteration. If the GPU is overwhelmed, the packet processing may not be executed immediately, causing a delay.

Method 3

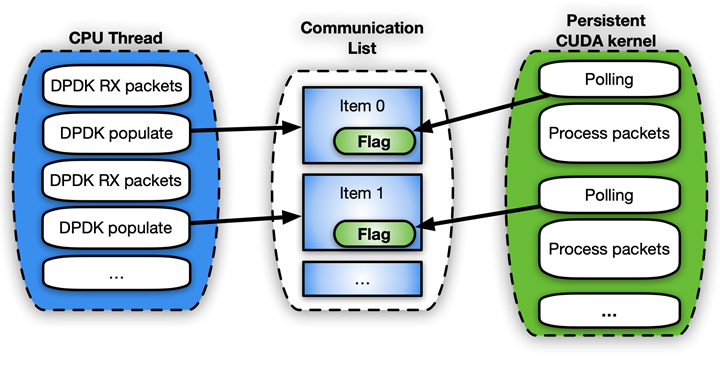

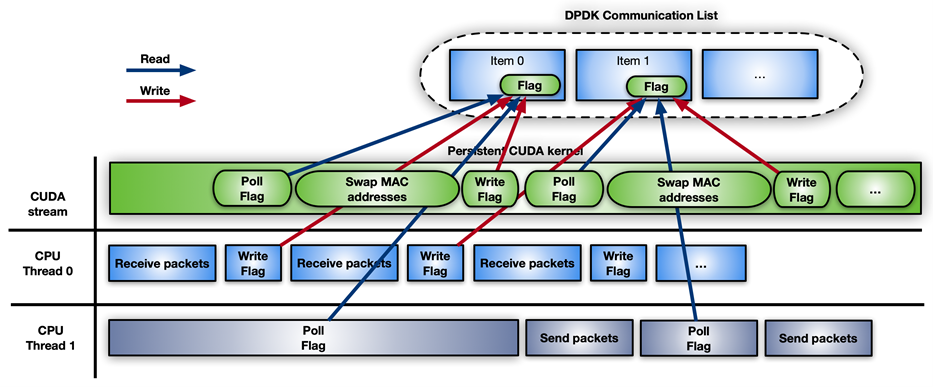

Figure 6 shows the third approach, which involves the use of a CUDA persistent kernel.

A CUDA persistent kernel is a pre-launched kernel that is busy waiting for a notification from the CPU: New packets have arrived and are ready to be processed. When the packets are ready, the kernel notifies the second CPU thread that it can move forward to send them.

The easiest way to implement this notification system is to share some memory between CPU and GPU using a busy wait-on-flag update mechanism. While GPUDirect RDMA is meant for direct access to GPU memory from third-party devices, you can use these same APIs to create perfectly valid CPU mappings of the GPU memory. The advantage of a CPU-driven copy is the small overhead involved. This feature can be enabled today through the GDRCopy library.

Directly mapping GPU memory for signaling makes the memory modifiable from the CPU and less latency expensive for the GPU during polling. You can also put that flag in CPU pinned memory visible from the GPU, but the CUDA kernel polling on CPU memory flag would consume more PCIe bandwidth and increase the overall latency.

The problem with this fast solution is that it is risky and not supported by the CUDA programming model. GPU kernels cannot be preempted. If not written correctly, the persistent kernel may loop forever. Also, a long-running persistent kernel may lose synchronization with respect to other CUDA kernels, CPU activity, memory allocation status, and so on.

It also holds GPU resources (for example, streaming multiprocessors) that may not be the best option, in case the GPU is really busy with other tasks. If you use CUDA persistent kernels, you really must have a good handle on your application.

Method 4

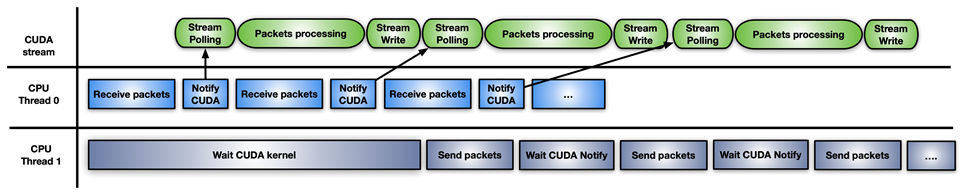

The final approach is a hybrid solution of the previous ones: use CUDA stream memory operations to wait or update the notification flag, with pre-launching on the CUDA stream one CUDA kernel per set of received packets.

The difference with this approach is that GPU HW is polling (with cuStreamWaitValue) on the memory flag rather than blocking the GPU streaming multiprocessors, and the packets’ processing kernel is triggered only when the packets are ready.

Similarly, when the processing kernel ends, cuStreamWriteValue notifies the CPU thread responsible for sending that the packets have been processed.

The downside of this approach is that the application must, from time to time, re-fill the GPU with a new sequence of cuStreamWaitValue + CUDA kernel + cuStreamWriteValue so as to not waste execution time with an empty stream not ready to process more packets. A CUDA Graph here can be a good approach for reposting on the stream.

Different approaches are suited to different application patterns.

DPDK and GPUdev

The Data Plane Development Kit (DPDK) is a set of libraries to help accelerate packet processing workloads running on a wide variety of CPU architectures and different devices.

In DPDK 21.11, NVIDIA introduced a new library named GPUdev to introduce the notion of GPU in the context of DPDK, and to enhance the dialog between CPU, network cards, and GPUs. GPUdev was extended with more features in DPDK 22.03.

The goals of the library are as follows:

- Introduce the concept of a GPU device managed from a DPDK generic library.

- Implement basic GPU memory interactions, hiding GPU-specific implementation details.

- Reduce the gap between the network card, GPU device, and CPU enhancing the communication.

- Simplify the DPDK integration into GPU applications.

- Expose GPU driver-specific features through a generic layer.

For NVIDIA-specific GPUs, the GPUdev library functionalities are implemented at DPDK driver level through the CUDA driver DPDK library. To enable all the gpudev available features for an NVIDIA GPU, DPDK must be built on a system having CUDA libraries and GDRCopy.

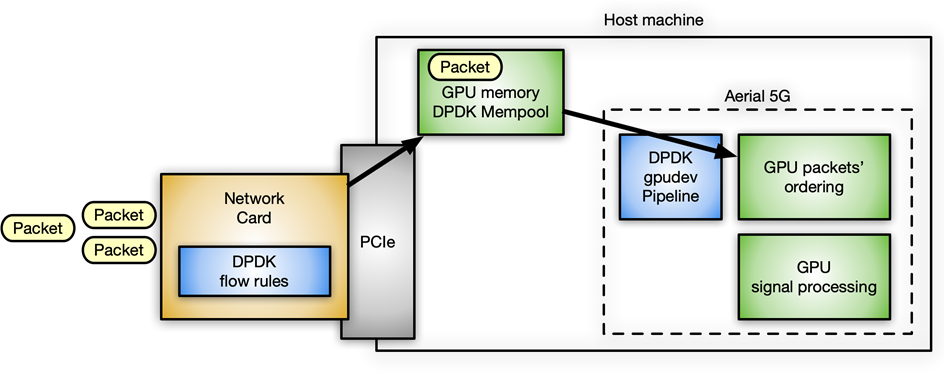

With features offered by this new library, you can easily implement inline packet processing with GPUs taking care of both data flow and control flows.

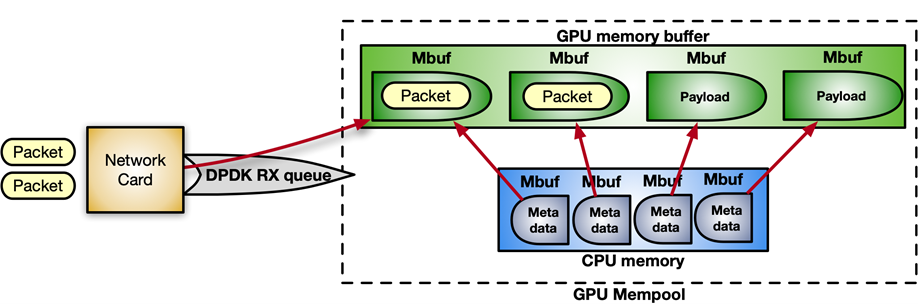

DPDK receives packets in a mempool, a continuous chunk of memory. With the following sequence of instructions, you can enable GPUDirect RDMA to allocate the mempool in GPU memory, registering it into the device network.

struct rte_pktmbuf_extmem gpu_mem;

gpu_mem.buf_ptr = rte_gpu_mem_alloc(gpu_id, gpu_mem.buf_len, alignment));

/* Make the GPU memory visible to DPDK */

rte_extmem_register(gpu_mem.buf_ptr, gpu_mem.buf_len,

NULL, gpu_mem.buf_iova, NV_GPU_PAGE_SIZE);

/* Create DMA mappings on the NIC */

rte_dev_dma_map(rte_eth_devices[PORT_ID].device, gpu_mem.buf_ptr,

gpu_mem.buf_iova, gpu_mem.buf_len));

/* Create the actual mempool */

struct rte_mempool *mpool = rte_pktmbuf_pool_create_extbuf(... , &gpu_mem, ...);Figure 8 shows the structure of the mempool:

For the control flow, to enable the notification mechanism between CPU and GPU, you can use the gpudev communication list: a shared memory structure between the CPU memory and the CUDA kernel. Each item of the list can hold the addresses of received packets (mbufs) and a flag to update about the status of processing that item (ready with packets, done with processing, and so on).

struct rte_gpu_comm_list {

/** DPDK GPU ID that will use the communication list. */

uint16_t dev_id;

/** List of mbufs populated by the CPU with a set of mbufs. */

struct rte_mbuf **mbufs;

/** List of packets populated by the CPU with a set of mbufs info. */

struct rte_gpu_comm_pkt *pkt_list;

/** Number of packets in the list. */

uint32_t num_pkts;

/** Status of the packets’ list. CPU pointer. */

enum rte_gpu_comm_list_status *status_h;

/** Status of the packets’ list. GPU pointer. */

enum rte_gpu_comm_list_status *status_d;

};

Example pseudo-code:

struct rte_mbuf * rx_mbufs[MAX_MBUFS];

int item_index = 0;

struct rte_gpu_comm_list *comm_list = rte_gpu_comm_create_list(gpu_id, NUM_ITEMS);

while(exit_condition) {

...

// Receive and accumulate enough packets

nb_rx += rte_eth_rx_burst(port_id, queue_id, &(rx_mbufs[0]), rx_pkts);

// Populate next item in the communication list.

rte_gpu_comm_populate_list_pkts(&(p_v->comm_list[index]), rx_mbufs, nb_rx);

...

index++;

}For simplicity, assuming that the application follows the CUDA persistent kernel scenario, the polling side on the CUDA kernel would look something like the following code example:

__global__ void cuda_persistent_kernel(struct rte_gpu_comm_list *comm_list, int comm_list_entries)

{

int item_index = 0;

uint32_t wait_status;

/* GPU kernel keeps checking exit condition as it can’t be preempted. */

while (!exit_condition()) {

wait_status = RTE_GPU_VOLATILE(comm_list[item_index].status_d[0]);

if (wait_status != RTE_GPU_COMM_LIST_READY)

continue;

if (threadIdx.x num_pkts) {

/* Each CUDA thread processes a different packet. */

packet_processing(comm_list[item_index]->addr, comm_list[item_index]->size, ..);

}

__syncthreads();

/* Notify packets in the items have been processed */

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

RTE_GPU_VOLATILE(comm_list[item_index].status_d[0]) = RTE_GPU_COMM_LIST_DONE;

__threadfence_system();

}

/* Wait for new packets on the next communication list entry. */

item_index = (item_index+1) % comm_list_entries;

}

}A concrete use case at NVIDIA that uses the DPDK gpudev library for inline packet processing is in the Aerial application framework for building high-performance, software-defined, 5G applications. In this case, packets must be received in GPU memory and reordered according to 5G-specific packet headers, with the effect that signal processing can start on the reordered payload.

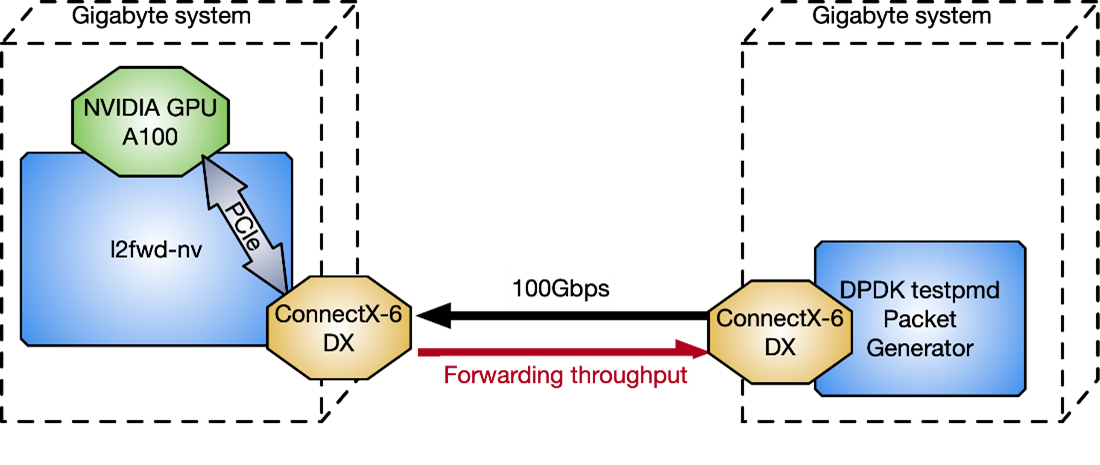

l2fwd-nv application

To provide a practical example of how to implement inline packet processing and use the DPDK gpudev library, the l2fwd-nv sample code has been released on the /NVIDIA/l2fwd-nv GitHub repo. This is an extension of the vanilla DPDK l2fwd example enhanced with GPU capabilities. The application layout is to receive packets, swap MAC addresses (source and destination) for each packet, and transmit the modified packets.

L2fwd-nv provides an implementation example for all the approaches discussed in this post for comparison:

- CPU only

- CUDA kernels per set of packets

- CUDA persistent kernel

- CUDA Graphs

As an example, Figure 11 shows the timeline for CUDA persistent kernel with DPDK gpudev objects.

To measure l2fwd-nv performance against the DPDK testpmd packet generator, two Gigabyte servers connected back-to-back, have been used in Figure 12 with CPU: Intel Xeon Gold 6240R, PCIe gen3 dedicated switch, Ubuntu 20.04, MOFED 5.4, and CUDA 11.4.

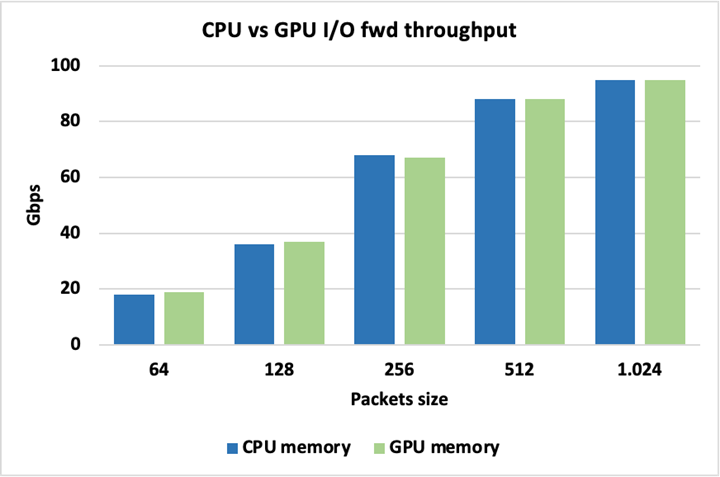

Figure 13 shows that peak I/O throughput is identical when using either CPU or GPU memory for the packets, so there is no inherent penalty for using one over the other. Packets here are forwarded without being modified.

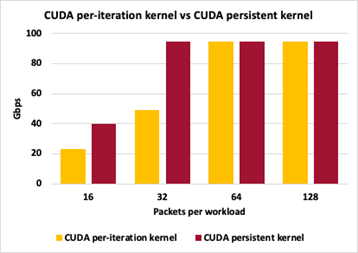

To highlight differences between different GPU packet handling approaches, Figure 14 shows the throughput comparison between Method 2 (CUDA kernel per set of packets) and Method 3 (CUDA persistent kernel). Both methods keep packet sizes to 1024 bytes, varying the number of accumulated packets before triggering the GPU work to swap packets’ MAC addresses.

For both approaches, 16 packets per iteration causes too many interactions in the control plane and peak throughput is not achieved. With 32 packets per iteration, the persistent kernel can keep up with peak throughput while individual launches per iteration still have too much control plane overhead. For 64 and 128 packets per iteration, both approaches are able to reach peak I/O throughput. Throughput measurements here are not at zero-loss packets.

Conclusion

In this post, I discussed several approaches to optimize inline packet processing using GPUs. Depending on your application needs, you can apply several workflow models to gain improved performance as a result of reduced latency. The DPDK gpudev library also helps simplify your coding efforts to achieve optimum results in the shortest amount of time.

Other factors to consider, depending on the application, include how much time to spend accumulating enough packets on the receive side before triggering the packet processing, how many threads are available to enhance, as much as possible, parallelism among different tasks, and how long the kernel should be persistent in the execution.